WAML Diversity and Early Career Librarian Scholarship Essay

Introduction.

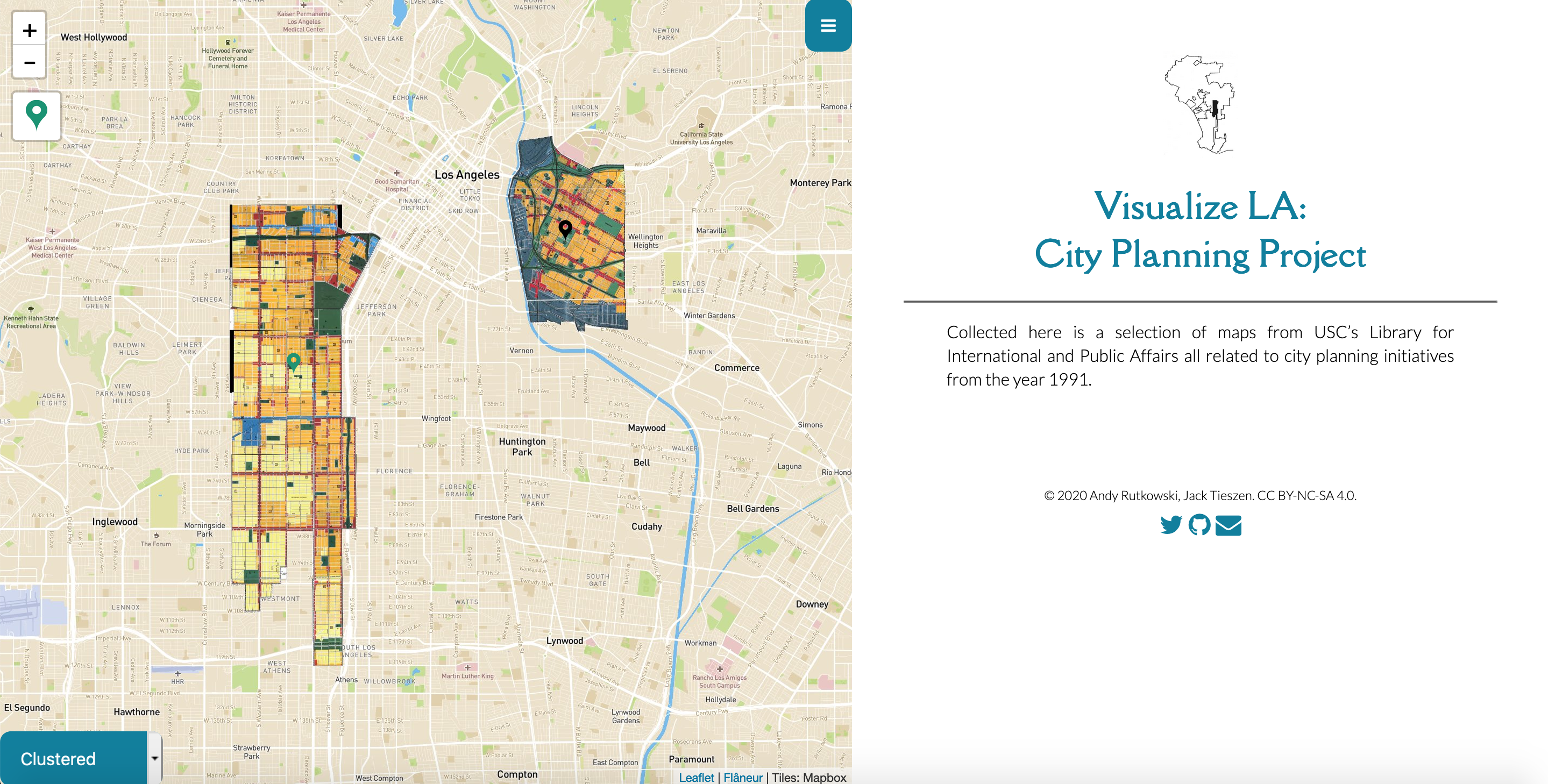

The mapping project that I have chosen for the 2020 WAML Diversity and Early Career Librarian Scholarship is the Planning Docs Digitization Project at the University of Southern California’s Library for International and Public Affairs. I chose this project because this was the end product of an internship that I had with Visualization Librarian Andy Rutkowski while I was working towards my MLIS at UCLA earlier in 2020. Due to this work, I am familiar with both the textual elements of the map and its contents as well as the methods that were used to publish the information. Concerning the scholarship’s focus on social justice and critical geography both the content of the planning documents and the project itself are valuable as each of them addresses topics as widespread and intersectional as access, poverty, and the city as it relates to the individual neighborhoods or fixed districts.

You can find the project here.

This webpage will first discuss the logistics of the project and how we digitized and published the materials with the concept of minimal computing in mind. Next, I will address the textual elements of the maps and the planning documents that provide the context to bring forth a further discussion of the intersectional issues mentioned above. Lastly, I will address the value of these two elements both on a grand social scale, but also individually as they affected me in the process of engaging with these artifacts during this project.

The Logistics of the Project.

The mapping project itself entailed taking a series of planning documents from the early 1990s related to the city of Los Angeles, digitizing them using already existing scanners within the library at USC, georeferencing the maps, and publishing these artifacts to an easily accessible website for those interested in researching these documents. The justification behind this project was mainly based on the fact that these artifacts were previously sequestered within a filing cabinet in a library office, and despite being available on the institution’s library database they weren’t easy to physically find. A concept that Andy Rutkowski and I settled on early into the project was to works

within the confines of minimal computing, which by definition is computing done under some set of significant constraints of hardware, software, education, network capacity, power, or other factors. What this meant for this project was that we constrained ourselves to utilize equipment and software that was either available such as the scanner used to digitize the documents (one could possibly use a smartphone or other, cheaper cameras to scan these files into pdf’s and still achieve a similar outcome), or free such as the open-sourced software utilized within the process of georeferencing and publishing these artifacts. The free software used was QGIS, an open-source geographic information system, Mapbox, an online map display customizer, and GitHub, a repository hosting site.

The project also granted me the ability to create a workshop designed to teach people without previous education how to accomplish the same product by using QGIS and GitHub to publish their own information or other digitized maps. We wanted to make the process of creating, digitizing, and publishing these maps as open and as cheap as possible to explain to potential researchers and future students of geography (and other disciplines) that this process is not only simple but also incredibly accessible to a large collective of people who may not have the funding to purchase ArcGIS, host their website, or to achieve an education that would allow them working knowledge of geographic information systems. With the workflow that we created, we wanted to be sure that anyone could take a map that they had/had access to and digitize it to a website without much issue or cost. This focus on limiting costs for accessibility ties into the textual information of the map as the planning documents deal heavily with the problems facing the city of Los Angeles in the early 1990s.

The Planning Documents.

Looking at the website and at the maps specifically, one would be able to read the plans and understand what zones were designated for what particular purposes. The key, showing up after pressing one of the various colored points on the map, indicates everything from specific land use (Residential, commercial, open space), circulation (Road, railways, bikeways), administrative boundaries (City and community boundaries), special boundaries (Opportunities areas, specific plans), and service systems (Schools sites, recreational sites, other facilities). The picture painted from the maps and their respective keys is of a city neighborhood that has various zones designated for these use areas. But the map itself is only one element of the story. As you scroll down from the key you notice the digitized documents related specifically to the plan and they express the full narrative of these various colors and why these plans are designed in the way that they are. Within the text of these planning documents, there are a variety of quotes that exemplify the socio-economic problems that exist within the city at that time along with the extent of these problems as seen from the perspective of a government body. On the first page of the South Los Angeles document the reader is confronted with this quote:

“Like central areas of most large cities, it is confronted with numerous physical, social and economic problems: the deterioration of housing, commercial development and public facilities and utilities; a declining tax base and rising tax rates; unemployment and crime; abandonment of not only homes but even whole neighborhoods. Fear of financial and social instability in these communities has influenced business, industry, and residents who can afford to do so to leave. The result is social and economic segregation and private, public, and institutional disinvestment. To compound the problem, public services seem to be less adequate than those provided elsewhere in the City.” (SC – 1).

This description seems similar to that of Henri Lefebvre’s description of the city core within the text Right to the City where he describes the city center as “overrun, often deteriorated, sometimes rotting” and needing to reassert itself as a strong central power within the confines of the space in order to prevent further deterioration (Lefebvre 9). This is an assertion that addresses the instability seen within inner parts of cities. Instability that is related to areas of socio-economic unrest, a lack of opportunity, and community flight that exacerbated segregation within the city and created the distinction between the inner cities and the suburbs/fringe cities throughout the decades in Los Angeles and beyond.

The plans reflect this increasing disparity between the “inner cities” and the suburbs/fringe cities, indicating that these latter areas have been more successful “in competing for and obtaining the major share of public utilities, facilities, and services as well as the investment of both the public and private sector” (SC – 1). These disparities and the problems associated with them, according to the text, were identified by the McCone Commission after the South Los Angeles riots in 1965, and yet despite this formal acknowledgment, there has been a significant lack in public or private attention/investment required “to bring about an improved physical, social and economic environment” (SC – 1). Essentially, to reassert these areas as valuable in order to stop the deterioration. The plan makes an imperative judgment that these issues need to be dealt with lest we allow the city to continue going down the route of creating a more distinct separation of classes between the inner-cities and the suburbs/fringe cities.

“It is beginning to be apparent that if deterioration is allowed to continue, the remainder of the City will be adversely affected. Blight will spread into adjacent communities and the entire City will be more and more burdened with increased expenditures to control crime and fight fires, to resolve health problems, to provide remedial educational programs, and to provide sustenance to more and more persons through public welfare programs. The vitality and health of South Los Angeles is essential to the future well-being of all of Los Angeles.” (SC – 1).

This quote from the planning document ties once again into Lefebvre’s writings on the city as he expresses that the city depends on the relations of immediacy, or more explicitly the relations between social organizations on a micro-scale (families/small organized bodies) and social organization on a macro level (a more powerful and regulated institution such as a government body). This he refers to as near order and far order (Lefebvre 26). To synthesize this discourse to relate to the planning document, the deterioration of the city center would eventually spread out due to the contiguous relationships in both physical and socio-political space. If the greater city (far order) doesn’t address this problem then it will likely affect communities (near order) extending past the original center of physical/economic “deterioration.” In this discussion near order and far order are intertwined within the construction of a city and therefore no one single area can be separated from the rest if it experiences a socio-economic blight. Further problems would only occur if those with means continued to spread out and separate themselves from the problems associated with the city as is.

The story that this map conveys with all of the information is bleak in contrast with the bright colors showcasing areas of leisure or employment. The segregation of the texts is a reflection of many theorists' claims such as David Harvey’s indication that we are increasingly living in “divided, fragmented, and conflict-prone cities,” a claim made in 2008 but stand true for these 90s documents (Harvey 9). However, despite these unfortunate claims I find that the story that this map conveys to be one of hopeful future work. The planning text states that “Steps must be taken to fully integrate our society, both socially and economically, by providing opportunities to those who have the fewest opportunities; this means housing, employment and educational opportunities everywhere and equal mobility for all” (SC -2). This is a confrontation to the process of socio-economic exclusion that allows for the separation and historical segregation of various collectives (racial, economic, etc.) within physical areas. The plans directly address these challenges in an attempt to “meet existing and anticipated needs and conditions; contribute to a healthful and pleasant environment; balance growth with stability; reflect economic potential and limitations, land development and other trends; provide for the facilities and amenities and promote a socio-economic climate which will result in stable and desirable neighborhoods for the residents of the District; and protect investment to the extent reasonable and feasible” (SC – 3).

This information, which comes only from the South Los Angeles planning documents but can be seen repeated in other planning documents not yet digitized within USC’s library, is inherently linked to the issues of social justice from the perspective of race and class, however, a critical analysis addressing intersectional issues of gender, sexuality, disability, etc., can go much deeper and this is why this particular set of maps/documents can be a good outline for addressing issues of equitable justice on a broader societal level. Social justice work, on a large scale, has historically used movements as a backbone for diving into critical analysis, of asking questions in geography such as “why does racism persist and how does it become inscribed in the ghettoized landscapes of US cities?” (Smith 8). Despite a noted decline in interest in critical geography over the years (according to Neil Smith in the text Marxism and Geography in the Anglophone World) our current volatile political and social climate has required a renewed interest in space as a method of enacting justice, and in order to analyze space in totality, one must use historical texts to address and criticize long-standing issues within areas of city planning (Smith 8). This series of planning documents and maps are certainly one of many that can be utilized for that renewed interest. It is important for both what it was and for what it can be used for in the future.

Broad Impact.

What makes this map impactful on a broader scale was discussed above. It is both its explicit implications within the text but also what it could be used for. I believe in the possibilities of maps for what they showcase and also in research to uncover inequalities through visualized means. What we see here represented on the map is a story of zones and how these zones affect specific communities. But the map is also important for what it lacks. What is missing from the record and what needs to be addressed to get a more in-depth story is where I think this series of maps and its contents are valuable for future use. Why is there a focus on alcohol zoning? How do the distinctions of public and private/quasi-private interests impact the growth or decline of these areas? What should have been addressed but wasn’t during this study? These are all important questions that open this map to further research, and that is just within the context of South Los Angeles as there are still nearly 40 more folders within USC’s library that require digitization and publication, opening up the process for further discoveries and questions. The project of digitizing and publishing the findings in an accessible manner allows for research and hopefully it will allow for other people to take on the mantle of digitizing their collections in simple, but effective ways as a means to represent marginalized stories. More critical forms of geography have historically raised questions of utilizing the discipline as a means to address ways to deal with societal problems and recent issues of over-policing in Black communities, joblessness due to the current global pandemic, and others should be addressed in the same manner. How must we take this history and continue to apply it from a modern perspective through looking at spatial data? This question I find engaging, which is what brought me into the field of map librarianship.

Personal Impact.

As I was working on this project during my internship, I began to interrogate geography and spatial information on a more critical level than what I had previously accomplished during my undergraduate tenure. During that time, I was focused too much on issues of health and population movement and wasn’t particularly interested in how social causes, economics, and politics affect the city and other areas. When I entered into graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles, I had no major plans of going into a cartographic or GIS librarian position as a future career trajectory, but the opportunity fell into my sights almost randomly after I completed the first year. Seeing as I had a background in GIS and was in the process of writing my major paper about academic libraries and space it felt right to engage with the USC project. As I began to address issues of accessibility with regards to the digitization and publishing aspect I started to engage in Map Librarianship a bit more closely by utilizing my academic training, reading the works of Joanne Patricia Sharp, Nicholas Blomley, Mei-Po Kwan, Richard Peet, and others to fully integrate my knowledge into a more critical perspective. Now that I’ve had a taste of the possibilities of this field through this project, I wish to pursue it further. The desire to investigate additional areas of social-spatial impact can be addressed using geography and now, more than ever, there is a need for this type of data to be visualized and studied as a boon for social justice in cities, communities, and institutions.

A quote that I came across during the writing of this web page exemplifies my intellectual curiosity and drive towards cartographic librarianship. Referencing a quote by the urban sociologist Robert Park regarding the city and its making/remaking relationship with mankind, David Harvey states: “The question of what kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be, what kinds of social relations we seek, what relations to nature we cherish, what style of daily life we desire, what kinds of technologies we deem appropriate, what aesthetic values we hold” (Harvey 1). What we wish and what we desire out of our shared social spaces as we move forwards in time is a major question that needs to be asked and to answer it fully or even to begin to address smaller implications of the question as they relate to our cities, our communities, and our institutions, then geography is a requirement. Furthermore, to research them, then the repositories that libraries and institutions hold through their special collections are key to the answers of a better future.

References.

Hamilton, Calvin. Wilson, Robert. Blossom, Glen. 1991. “South Central Los Angeles Plans.”

Harvey, David. 2008. “The Right to the City.” 16.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1968. "Right to the City." Routledge.

Smith, Neil. 2001. “Marxism and Geography in the Anglophone World.” Geographische Revue, 17.